The Biden administration decided to return the Iranian nuclear agreement that was withdrawn by the Trump administration in 2018. It is expected that the revitalization of the deal would enable Iran to throw the United States (US) sanctions off and to reach the blocked funds. For regional countries, Iran had been instrumentalizing these funds with the aim of boosting its influence in the region. On the other hand, the fact that the US has withdrawn its security umbrella from its regional allies urged regional countries to have embarked on the formation of a new alliance without the US.[1] In particular, the Biden administration did not take a sharp stand against the Houthi movement, which the US delisted as a foreign terrorist organization. Against the backdrop, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has been in search of pulling Syria and Lebanon out of Iranian influence gradually and circling them in the Arabic sphere.[2] In addition, Gulf countries signed the al-Ula declaration last year and formally ended the dispute with Qatar.[3]

Looking at the big picture, it seems that a new axis against Iran was formed with the US, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia following the former US President Donald Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia in 2017. During the tenure of the Trump administration, almost every country in the Middle East tried to have a close relationship with Israel in order to assure the security of their regimes by means of US assistance.[4] The new axis against Iran was involved in Israel, UAE, and Bahrain with Abraham Accords in 2020. Israel and regional countries strive to adopt a new order in which Iran could play an aggressive role as soon as the nuclear talks are in progress. Indeed, Tehran had used the nuclear agreement with the Obama administration to strengthen its presence in Syria and Iraq.[5] As part of this process, Türkiye and Israel decided to solve the rift in their relations. The relationship between two countries has witnessed a relationship with ups and downs as Turkey criticizes Israel’s aggression to the Palestianian people’s rights and Israel problematizes Türkiye’s relations with Hamas. These two issues structurally keep the Türkiye-Israel relationship in a restricted environment.

2. Evolution of Israeli Foreign Policy

The founding doctrine of Israeli foreign policy, The Periphery Doctrine (PD), sorted the regional countries into two groups. The first group was the Arab countries, which were seen as an existential threat to Israel’s security. The countries in the first group had advocated the ideal of Pan-Arabism with the dynamism of the Nasserist wave. In the second group, there were minority groups in Arab countries and non-Arab peripheral countries such as Türkiye and Iran. According to the periphery strategy, Israel could cooperate against the existential threat to Israel from Arab countries.

However, Israel’s perception of security has undergone a dramatic evolution in the process. While Israel has signed normalization agreements with the two states (Egypt and Jordan) with the longest border, there is a complete internal disturbance in Israel’s northern neighbor countries, Syria and Lebanon. Iran-backed groups in Syria and Lebanon have become the main threat to Israel. In the historical process, Israel’s threat perception has moved from the first group of countries to the second group of other countries. Yoel Guzansky accounts for this situation through the “Reverse Periphery Doctrine” (RPD).[6] This concept states that Israel’s most prominent regional threat comes from Iran and Türkiye. Contrary to the Periphery Doctrine, Israel develops its relations with the countries in the first group in response to threats from the second group.

Although Guzansky puts Türkiye and Iran in the same category, there are essential differences between the historical course and current situation of Israel-Türkiye relations and Iran-Israel relations:

- The Iranian Islamic Revolution has been a severe breaking point regarding Iran-Israel relations. Although Türkiye-Israel relations followed a fluctuating graphic, they did not break apart.

- Even in the most challenging periods of relations, cooperation between the two countries in specific areas such as trade and intelligence continued steadily. The doors of dialogue between Türkiye and Israel have never been completely closed.

- While Iran and Israel act with opposite goals in conflict areas such as Syria and Lebanon, there are common goals between Türkiye and Israel on these issues.[7]

- Despite continuing relations with Hamas, Israel continued to get closer with Türkiye.[8] On the other hand, Iran is considered a monolithic threat by the Israeli security elite, along with its proxies.

When considering these points, it is necessary to evaluate the relations between the two countries with their unique characteristics.

3. Factors Affecting Türkiye-Israel Rapprochement

3.1: Security: When the history of relations between the two countries is examined, we can see that common security concerns constitute a basis of bilateral relations. In the 1990s, when relations were at their peak, the bilateral ties focused on defense and security cooperation.[9] Although the military’s domination over the Turkish political life gradually disappeared with the AK Party era, intelligence cooperation and bilateral trade continued even in the tensest periods of relations between the two countries.[10]

Israel is one of the countries most affected by the shrinking of the US security umbrella in the Middle East due to the US withdrawal from the region. Unlike Israel, the other allies of the US follow a two-way preventive strategy against Iran based on both dialogue and defense. For example, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, on the one hand, develop new cooperations with countries such as Russia and China in trade and defense areas. On the other hand, they strive to maintain their relations with the US to a large extent. Alternatively, Israel continues to implement a melt containment strategy on Iran. That’s why Israel attempted to normalize some Arabic countries. Notwithstanding, the Arabic countries which have normalized their relationship with Israel have different expectations from the normalization process with Israel.[11] Israel interprets the process as an attempt to create a regional defense bloc against Iran. Although this goal of Israel does not fully comply with the regional countries’ goals, the fact that Israel somehow surrounded Iran with diplomatic steps is considered a success.

Türkiye is of great importance in Israel’s strategy to contain Iran. When evaluating the spheres of influence of the two countries, Türkiye and Israel have been on the brink of the rapprochement. For instance, the two countries’ common interests in Azerbaijan seriously disturb Iran.[12] Türkiye and Azerbaijan are threatened in the video allegedly shared from a channel belonging to the Revolutionary Guards.[13] In addition, Reuters claimed that the Iranian missile attack targeted a villa in Erbil where the negotiations of Israeli gas transfer to Türkiye via the KRG were held.[14] All of them point to Türkiye’s strategic position against the Iranian threat in the eyes of Israel.

3.2: Economy: It is noteworthy that even in the most difficult periods of the Türkiye-Israel relationship, the trade volume between the two countries has steadily been increasing. Many analyzes published in the Israeli media about the rapprochement argue that the recent depreciation of the Turkish Lira has pushed Ankara to a more moderate approach to its foreign policy. In the press statement held after the bilateral meeting with Herzog, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan emphasized the size of the trade volume between the two countries and announced the goal of reaching 10 billion dollars in 2022. Before and after the meeting, business people from both countries made mutual visits.[15]

There are many Turkish companies operating actively in Israel. Especially in the building materials and construction sector, Turkish companies are the second-largest supplier after China.[16] In addition, the Jenin Organized Industrial Zone (OIZ), which is still under construction and carried out by the Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Türkiye (TOBB) Industry for Peace initiative, has substantial potential in terms of the two countries’ trade volume.[17] Although it is a project that has been going on for a long time, essential steps have been taken in the last period to complete the project, and it is expected that Jenin OIZ will become operational at the end of 2022.[18]

3.3: Politics: Türkiye-US relationship has played an important role in the recent rapprochement of Türkiye-Israel relations. The Turkish ambassador to Washington, Hasan Murat Mercan, who had critical contacts with leading figures of the Jewish Community in the US, considerably impacted the rapprochement process.[20] In addition, a joint memorandum was signed between the Turkish-American National Steering Committee (TASC), known for its close relations with Türkiye, and the Orthodox Jewish Chamber of Commerce (OJC). The declaration included items such as combating antisemitism and islamophobia and promoting bilateral trade and business relations. Yet TASC had to announce its withdrawal from this declaration due to public reactions.[21]

This active role played by Mercan’s contact with Jewish groups in the US point to one of the main motivations that pushed Türkiye to get closer to Israel. The Tel Aviv administration and Jewish groups in the US significantly impact the Washington administration. The step towards rapprochement with Israel and Jewish groups was taken to soften the US-Türkiye relations, which entered a bad period with the Biden administration taking office. In this new period, the regional countries act on a bilateral balance to maximize their interests. For pragmatic reasons, the regional countries seek to enhance their relations with those countries with disagreements. Because of the new regional strategy of the US, the possibility of Iran returning to the nuclear agreement, the increasing Iranian threat in the region, and the Russia-Ukraine war, many uncertainties emerge for the future of the region.

While a new regional order is taking shape, Türkiye is following a pragmatic approach by making minimum concessions from its principles. Türkiye condemned the terror attacks at the lowest diplomatic level to protect relations with Israel in terms of its interests. Conversely, Türkiye’s ministry of foreign affairs censured Israel’s aggressions against the Palestinians during Ramadan month, which reflects the balance of principle-interest. Finally, the Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu emphasised that Türkiye’s relations with Israel depend on Israel’s Palestinian policies. Türkiye adheres to the principle by balancing its interest.

3.4: East Mediterranean and Energy: One of the main topics of the Türkiye-Israel rapprochement is undoubtedly the Eastern Mediterranean and Energy issue. When Türkiye-Israel relations were tense, Israel sought to develop diplomatic ties alternative to Turkey. In this process, an anti-Türkiye bloc was raised in the Eastern Mediterranean. Israel established a tripartite framework in 2016 with Greece and the Greek Cyprus administration to improve defense and economic ties. The cooperation deepened much around energy diplomacy. Signed in 2020 by the three countries, the East-Med project traced out an undersea conduit to carry Israel’s Leviathan gas field, which, with reserves of 620 billion cubic meters, could supply 10-12 billion cubic meters a year to Europe via Cyprus and Greece.[22] However, the project collapsed in January 2022 as the Biden administration rescinded US support.

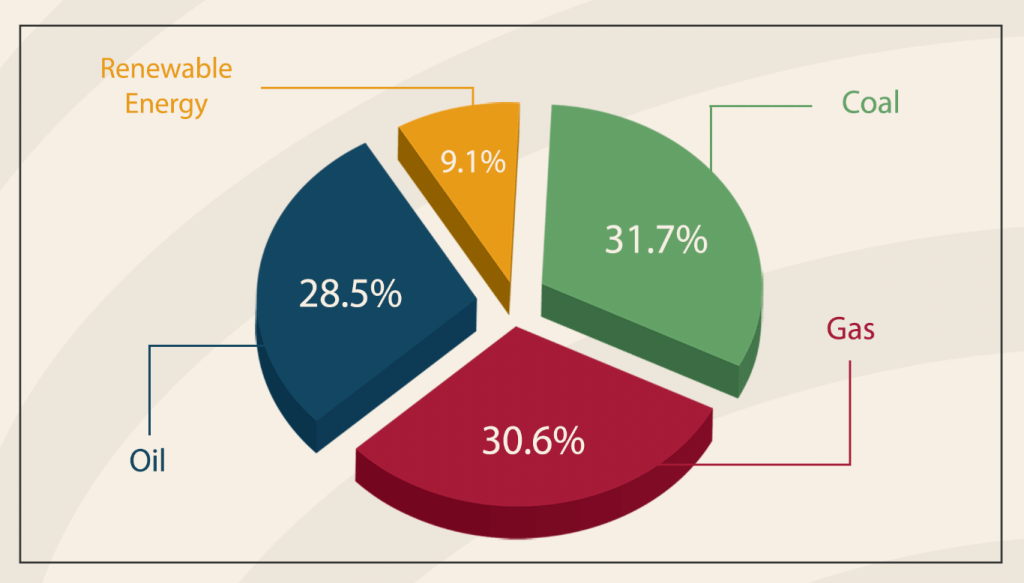

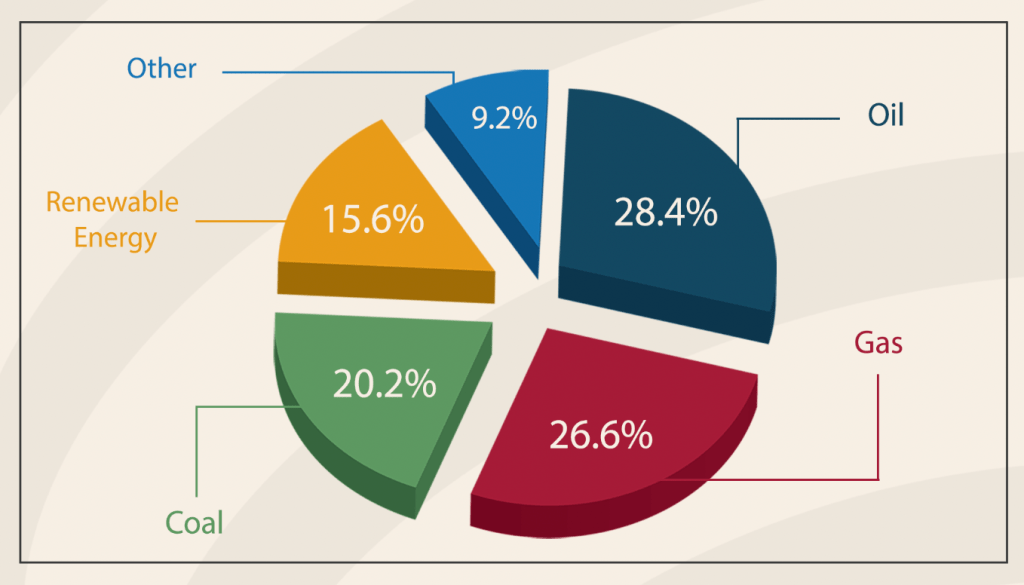

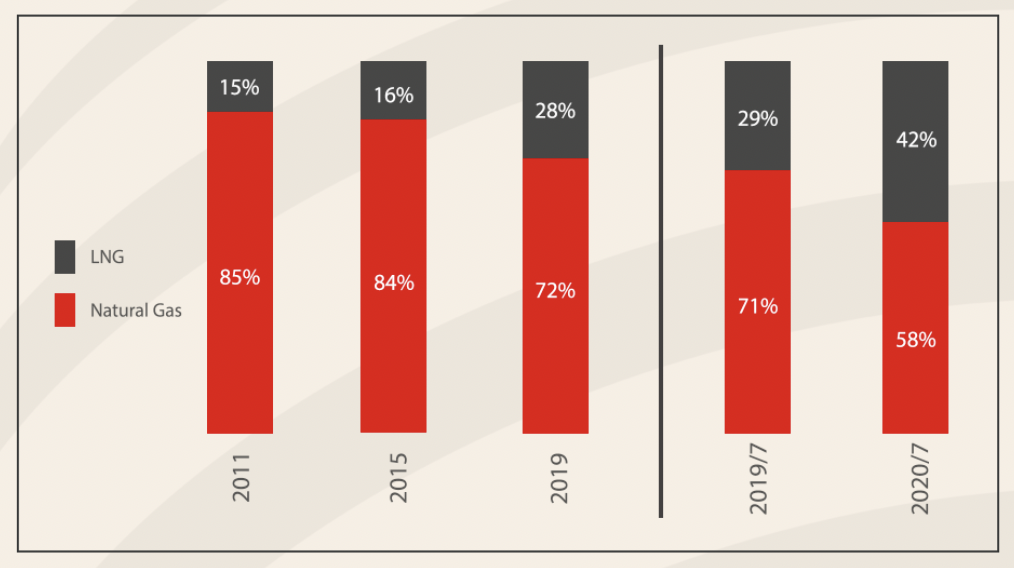

With the Russia-Ukraine war, alternative energy sources to Russian gas in energy security have come to the top agenda for Western countries. One of the alternatives is Israeli transfer to Europe to ensure production stability in Israel’s natural gas fields.[23] A possible pipeline to bring the Israeli gas to Europe through Türkiye has been recently seen technically and fiscally as the best feasible solution. The inadequacy of Israeli gas to meet the needs of Europe (326 billion cubic meters a year) required to add the gas extracted from the countries of the region to this line.[24] The pipeline through Türkiye would run around 500 kilometers and cost up to $1,5 billion to build, while the EastMed project has envisioned a 1,900-kilometer pipeline running from Israel to Cyprus and then to Greece and Italy at the cost of some $7.9 billion.[25] On the other hand, Israel does not want to risk a rupture with Greece and the Greek Cyprus administration.[26] Indeed, there are disagreements in the East Mediterranean, such as continental shift, maritime boundaries, and Cyprus problem to improve gas projects.[27] Because of leading the anti-Türkiye bloc, Israel thinks that developing its relations with Türkiye at the expense of these countries will seriously damage its international image and credibility.[28] In the last instance, the Turkish route to carry Israeli gas to Europe has the above-noted actual or potential problems in the East Mediterranean.[29] The other caveat of transfer via pipeline is that the EU’s vision on the climate crisis aims to decrease the gas share in its energy basket by 25 percent by 2030 and zero it out by 2050.[30] Consequently, Europe’s LNG imports have considerably increased.[31]

Israel also considers different alternatives in terms of energy transfer. Israel could plan to pipe its gas to Egypt’s liquefied natural gas plants for conservation of LNG and export by ship to Europe, regarded as the only way to overcome the political obstacles.[32] In this case, Israel would use Egyptian LNG facilities or build a liquefaction plant in the Leviathan field. As another alternative, EuroAsia Interconnector, a project carried out jointly by the Israel-Greek Cypriot Administration, is pointed out.[33] This project aims to integrate the electricity infrastructure of the three countries. It is envisaged that the Israeli gas transfer to Europe would be drawn on electricity generation. Similar to the EastMed project, there are some question marks about this project in terms of cost, implementation, and construction time.

4. What does the Turkish-Israeli relationship put in the regional issues?

The rapprochement of Türkiye and Israel will not change Türkiye’s current position on the Palestine issue and particularly Türkiye’s Hamas policies that Israel problematizes. Türkiye stressed that the Israel administration should not pursue policies that would jeopardize the two-state solution and not prevent the TIKA and the Turkish Red Crescent from carrying out activities in the region to improve the living conditions of the Palestinians.[34] Türkiye underlined the importance of the historical status of Jerusalem and the preservation of the religious identity and sanctity of Masjid Al-Aqsa. It is remarkable considering Arab leaders signing normalization deals with Israel failed to give importance to these issues.[35] So far, the new Israeli government has not put forward a game-changing policy related to both settlements and the two-state solution.[36] Finally, Israel urged Ankara to take some steps against the presence of Hamas leaders in Türkiye before launching reconciliation talks.[37] Türkiye views Hamas as the official representative of the Palestine people. Therefore, Türkiye has not taken steps backward in its relationship with Hamas, even when it comes to recalibrating the relationship between Ankara and Tel Aviv.

Striving to rein in Iranian influence, the UAE, Bahrain, and recently Jordan and Egypt seek to reduce the vacuum in Syria by normalizing relations with Assad. Israel is aware that Iran will preserve its influence via Hezbollah, seen as a vital foe by Israel in Syria. Given the situation in which the Assad regime is unable to control the entire country, Israel would keep open a dialogue with the PYD that Türkiye designated a terrorist organization to oppose the consolidation of the Iranian presence.[38] As a result, the rapprochement of Türkiye and Israel does not converge the two countries’ interests in Syria. Even Israel’s aid to the PYD could deteriorate the normalization of Türkiye and Israel. Israel not merely denounced Türkiye’s operation in northern Syria in 2019 but also expressed its support for the independence referendum in Iraq’s Kurdish region in 2017.[39]

A series of regional summits were organized to generate an alliance between Israel and Arabic countries. The aim of these summits is to discuss how the regional countries counterbalance Iran in the environment of the new regional dynamics resulting from the continuation of the American pivot to Asia. In one of these meetings, the Negev summit, the main agenda of the attendees was “Iran issue.” Although Egypt, UAE, and Morocco expressed their support for the two-state solution that proposed a framework for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, they have come closer with Israel to achieve their interests.[40] Türkiye’s rapprochement with Israel and UAE could mean cementing ties with countries that could counterbalance Iran. The expectation of a more aggressive Iran may have been a catalyst for the rapprochement of Israel and the UAE with Türkiye. Although Turkish officials spoke out that their relationship with Israel is not an alliance against Iran, it is expected that Türkiye and Iran will be rivals in Syria and Iraq. Türkiye-supported soldiers of the Syrian National Army have faced Iranian-backed Shia militias in Idlib, Syria. In addition, Iran seeks to keep Türkiye busy in the north of Iraq with the PKK; Türkiye has brought the Sunni parties together after they won a substantial number of seats.[41] Türkiye also is interested in boosting its natural gas cooperation with the Kurdish regional government. This is to say that Türkiye has a desire to reduce its energy dependence on Iran.[42] Amidst the rivalry between Türkiye and Iran, the Turkish-Israeli relationship might develop in intelligence cooperation in the region. In fact, events first in Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020 and then in Afghanistan in 2021 reapproached the Turkish-Israel relationship before the war in Ukraine started.

5. Conclusion

The recent activities of Israel and its allies in the region can be considered as preparation steps for a new Middle East process without superpowers. Parallel to the US’s strategy of withdrawing from the region, there has been a severe decrease in the security guarantees offered by the US to the regional countries, which has pushed them to seek new ones. This process underlies the formation of a moderate foreign policy atmosphere. Whereas the anti-Iran axis has ostensibly countered Iran, the main target of the axis was initially also Türkiye in accordance with leaked information from meetings between the relevant countries.

Since 2016, when Türkiye and Israel declared their ambassadors as persona non grata, Israel has pursued a foreign policy against Türkiye’s vital interest in the region. Israel has cooperated with Greece and the Greek Cyprus administration in the East Mediterranean, supported the attempted independence referendum of Kurds in Iraq, and ultimately cheered on the US’s confrontation against Türkiye. In 2016, Türkiye and Israel had discussed a way to import Israeli gas as part of a reconciliation deal after years of tensions resulting from Israel’s Gaza flotilla raid in 2010. However, the negotiations collapsed in 2018 over Israeli violations at Jerusalem and Gaza.[43] We can conclude that the Turkish-Israeli relationship would not deepen unless Türkiye cut off relations with Hamas on the one hand and Israel minded Palestinians’ rights on the other hand.[44] As in the past, the Türkiye-Israeli relationship could be limited to bilateral trade.

References

- https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/analiz/orta-doguda-abdnin-yer-almadigi-yeni-ittifak-arayislari-gundemde/2556453

- https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/analiz/orta-doguda-abdnin-yer-almadigi-yeni-ittifak-arayislari-gundemde/2556453

- https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/op-ed/change-in-turkish-foreign-policy-toward-the-middle-east

- https://fikirturu.com/jeo-strateji/turkiye-israil-normallesmesinin-yeni-dinamikleri/

- https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/columns/the-rising-turkey-effect-in-the-gulf

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mepo.12579

- https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-israel-share-common-interest-in-syria-netanyahu-30193

- https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/article-696651

- https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/539675

- https://www.bbc.com/turkce/live/haberler-dunya-55444226

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/for-israel-the-negev-summit-was-all-about-iran-for-other-participants-not-so-much/

- https://iramcenter.org/iran-azerbaycan-geriliminin-arka-plani/?send_cookie_permissions=OK

- https://www.trhaber.com/iran-dan-skandal-turkiye-videosu-acik-acik-tehdit-ettiler-video,5461.html

- https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/exclusive-iran-struck-iraq-target-over-gas-talks-involving-israel-officials-2022-03-28/

- https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/turk-ve-israilli-is-insanlari-karsilikli-ticareti-artirmayi-hedefliyor/2527504

- https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/israel-design-and-construction

- Türkiye-Palestine trade is evaluated within the Türkiye-Israel trade volume.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nZIfgk_EB-M

- https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=Dis-Ticaret-104

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/behind-israels-rekindled-flame-with-turkey-a-rabbi-with-a-penchant-for-matchmaking/

- https://twitter.com/ourtasc/status/1440823412243382274

- https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/03/can-turkey-benefit-europes-quest-reduce-russian-gas

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/05/business/energy-environment/israel-natural-gas-offshore.html

- https://menaaffairs.com/turkish-israeli-rapprochement-cooperation-and-problem-areas/

- https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/01/could-new-israeli-gas-pipeline-bridge-long-standing-rift-turkey

- https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-turkey-intelligence-closer-gas-pipeline-ahead-may

- https://www.orsam.org.tr//d_hbanaliz/turkiye-israil-iliskilerinde-yeni-gelismeler-ve-israilin-surece-bakisi.pdf

- https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001405438

- https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/03/no-magic-tap-europe-replace-russian-gas-turkey

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0773&from=EN , p. 5.

- https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/01/could-new-israeli-gas-pipeline-bridge-long-standing-rift-turkey

- https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001405438

- https://jiss.org.il/he/lerman-the-presidents-game/

- https://menaaffairs.com/turkish-israeli-rapprochement-cooperation-and-problem-areas/

- https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20220311-turkiye-did-not-discard-the-palestinians-to-repair-ties-with-israel/

- https://menaaffairs.com/turkish-israeli-rapprochement-cooperation-and-problem-areas/

- https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-turkey-intelligence-closer-gas-pipeline-ahead-may

- https://www.inss.org.il/publication/northern-arena-2022/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/10/25/what-is-behind-the-israeli-outrage-over-turkeys-syria-operation

- https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/analiz/zirvelerin-golgesinde-orta-doguda-degisen-politikalar/2554441

- https://www.trtworld.com/opinion/a-new-era-of-turkish-iranian-competition-may-be-on-the-horizon-55209

- https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/04/will-renewed-interest-iraqi-kurdish-gas-fuel-turkey-iran-rivalry

- https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/us-tells-israel-it-no-longer-supports-eastmed-pipeline-project-report

- https://www.orsam.org.tr//d_hbanaliz/turkiye-israil-iliskilerinde-yeni-gelismeler-ve-israilin-surece-bakisi.pdf

This series of studies review the remarkable developments in Türkiye’s international, regional, and internal status over the last five years (2015-2020) that witnessed qualitative and fundamental changes, including the failed coup in 2016, the restructuring of the Turkish State, the referendum, and transforming the government into the Presidential System.

There were also many international and regional changes— most notably, Donald Trump becoming the United States President and the changes in the States Administration’s priorities after Joe Biden took over. It is equally important to mention the effective direction of Türkiye’s foreign policy towards international issues such as Syria and Libya and its increasing role in Africa and Central Asia.

Finally, the economic, social, and political changes imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

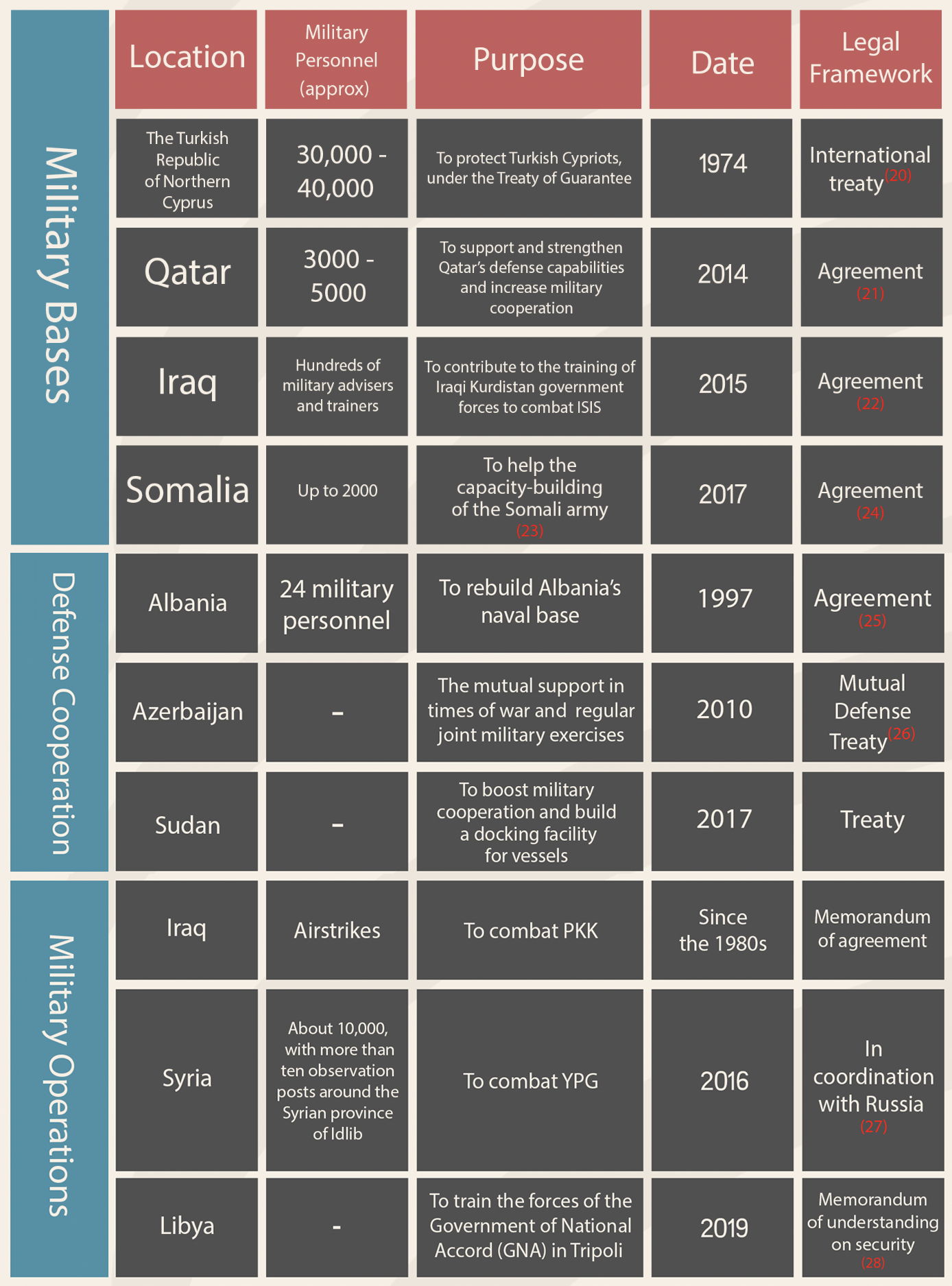

Our studies cover Türkiye’s energy, military industrialization, foreign relations, internal status, economy, external military interventions, and military bases beyond national borders.

As Türkiye faces many challenges while moving forward, we hope to shed light on the facts of Türkiye’s current regional and international position compared to five years ago.

Dr. Mustafa Al-Wahaib

Director of Anadolu Center for Near East Studies

1. Introduction

Türkiye’s foreign policy has undergone significant changes since 2015 due to the various developments in the country’s political and diplomatic positions.

Domestically, the Turkish foreign policy course was severely affected by the failed coup in 2016 and the transition to the presidential system in 2017.

Internationally, Türkiye has been involved in many issues related to the unstable region, like the conflict over energy resources, the delimitation of maritime borders in the Eastern Mediterranean, and military intervention abroad.

It is also important to mention Türkiye’s stance towards the Arab Spring and its support for Qatar during the Gulf Crisis, which critically affected its relations with some Gulf states, such as Saudi Arabia.

In this study, we comprehensively analyze Türkiye’s foreign relations with regional and international powers since 2015.

Although there are some countries that have a constant relationship with Türkiye, we found it important to cite them in the appendix of our study.

2. Key Drivers of the Turkish Foreign Policy

Identifying the so-called “inputs and outputs” as a tool of analysis, in addition to the traditions and experiences that form the constants of the country’s foreign policy, is essential in studying external relations. Furthermore, we apply the principle of variables to analyze the changes in the foreign policy of Türkiye.

In this context, Türkiye’s foreign policy is shaped by a variety of factors:

1- The political ideology of its governing elite (i.e., Kemalism).

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s ideological framework laid out the path that Türkiye’s foreign policy would follow, regardless of the different orientations of the successive Turkish governments.

The Kemalism principles include the following:

– Secularism:

In order to maintain a modern and more comprehensive society, secularism was considered a necessary component. It covered the political and governmental, as well as the cultural life.[1] Thus, according to Atatürk’s principle, the state may not build or adopt internal or external policies on a religious basis as in the past.

– Nationalism

As defined by Atatürk, geographical, political, cultural, and historical unity is the framework of Nationalism. There are also influential factors that established the Turkish Nation, including the unity in political existence, language, origin, ancestry, and common history.[2]

– Republicanism

Republicanism was the main principle of Atatürk’s revolution. It became the basis of the new Turkish state and has been preserved in its constitutions since 1924. Atatürk said that “the form of government which provides the most modern and logical application of the principle of democracy is the republic, which is the most appropriate administration to the nature and customs of the Turkish nation.”[3]

2- The History Factor:

Turkish foreign policy is based on the Ottoman Empire’s cultural and historical context. Its legacy contributed to the revival of Türkiye’s regional role, especially with Islamic and Arab countries. The consequences of this legacy are fundamentally reflected in Türkiye’s foreign policy, as well.[4]

3- The Geopolitical and Geostrategic Location

Türkiye’s privileged geographic location— a land bridge linking Europe and Asia— is a key driver in its foreign policy. However, it makes it more vulnerable to international developments and imbalances, and as put by former Prime Minister Mesut Yilmaz, it created the “national security syndrome.”

In this context, Türkiye’s foreign policy and security were affected by the repercussions of the conflict in its immediate regional neighborhood. This included the dissolution of the Soviet Union; the continued development of Eastern Europe; the crises in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo in the Balkans; the conflicts over Nagorno-Karabakh, Chechnya, and Abkhazia in the Caucasus; and the possibility of an independent Kurdish state in northern Iraq after the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

As a part of the Middle East, Türkiye has experienced general insecurity caused by the instability in the region, such as the Arab-Israeli wars, the first and second Gulf wars, and the state of the security vacuum and conflicts after the Arab Spring revolutions.[5]

2.1 Constants of Turkish foreign policy

The constants in foreign policy define the state’s fixed orientations toward regional and global issues.

The constants in Turkish foreign policy can be sorted as follows:

- NATO Membership: maintaining its membership in the largest military alliance in the world.

- Affiliation to Europe: Türkiye is a founding member of almost all European institutions, including the Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

- The Strategic Partnership with the United States: the compass of Turkish foreign policy has been consistent with the direction of the United States since the founding of the modern Turkish Republic.

- Expansion into Central Asia and the Caucasus: due to the linguistic and ethnic ties, Türkiye has a constant foreign policy toward the Turkish republics (Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan) in Central Asia and the Caucasus region.

- Black Sea security: relations with Russia and the safety of the Black Sea form a strategic focus in Türkiye’s foreign policy.[6]

2.2 Changes in Turkish Foreign Policy

In terms of foreign policy, change is a political phenomenon that includes a wide range of relative adoptions that can be simple but frequent and do not affect the country’s main course of foreign policy. The change, however, can be radical, not frequent, and requires restructuring of foreign policy and persuading the bureaucratic government agencies and society (if the system is democratic) to bring about this change.[7]

“According to the regional and international political variables, the Middle East and the Balkans are the most critical files that witnessed Türkiye’s foreign policy change.”

2.2.1 The Middle East

Türkiye-Arab relations were characterized by political stagnation in the 1950s, but they changed relatively along with the fall of the Soviet Union. Notably, a rapprochement with Arab and regional countries emerged with the AK Party’s arrival to power.[8]

2.2.2 Russia and the Balkans

Enmity has always prevailed in Turkish-Russian relations. During the Cold War, the confrontation increased after Türkiye sided with the Western camp and joined NATO to face the Soviet expansion in the Middle East and Asia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, relations between Russia and Türkiye started to take a significant role in their foreign policy.[9] This change was evident through the implementation of gas pipeline projects to export Russian gas to Türkiye.[10] During the AK Party’s rule, the value of trade exchange between the two countries increased.[11]

During the Cold War, the Turkish foreign policy paid particular attention to the Balkans region as it was considered a forward base for the Western bloc. Although this strategic importance was subjected to fluctuations caused by political influences, Türkiye benefited greatly, and the Balkans became a priority for Türkiye during the war in Bosnia—that priority declined after the fall of the Soviet Union, the end of the Bosnian war, and the restoration of stability in the region.[12]

2.3 Turkish Foreign Policy Strategies

Türkiye’s foreign policy is based on three main strategies:

2.3.1 Peace at Home, Peace in the World

Since the state’s founding, Türkiye’s international engagement has been influenced by the Peace at Home, Peace in the World strategy, formulated by the founder of the republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[13]

The strategy is based on resorting to peace in foreign relations by adhering to international law. Accordingly, Türkiye followed that tactic to maintain its independence during the major powers’ wars in Europe, a disengagement that enabled Türkiye to avoid the mandate in the event of its defeat.[14]

2.3.2 Zero Problems with Neighbors

Articulated by former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, the Zero Problems strategy aims to establish friendly relations with the region’s countries based on the following principles:

- The balance between security and freedom: that the freedom of expression and democracy should be protected in a way that is not detrimental to the state

- Zero problems with neighbors: like ending the problems of Syria and Cyprus, and normalizing relations with Armenia

- Multidimensional foreign policy: not relying on one international party, i.e., the Western camp, and openness to the East as well, in a way that achieves balance and guarantees Turkish interests

- Active regional policy: strengthening ties with regional countries and activating the Turkish role in the region

- New diplomatic style: abandoning the long-standing differences that dominate the foreign policy agenda and drain its energy in international relations

Work on this strategy started after the Justice and Development Party’s rise to power in 2002, and it has been implemented in various initiatives, such as addressing the Cyprus problem, curbing military actions in Syria, normalizing relations with Armenia, and strengthening bonds with developing international regions such as Asia, Latin America, and Africa.[15]

“Türkiye maintained a soft power diplomacy strategy that is focused on avoiding interference in other countries until 2015.”

2.3.3 Blue Homeland (Mavi Vatan)

The concept of the Blue Homeland Doctrine emerged from a plan drawn up by Admiral Cem Gürdeniz in 2006. It was later crystallized by retired Admiral Prof. Dr. Cihat Yaycı, Head of Naval and Strategic Research at Bahçeşehir University.

Representing Türkiye’s Hard Power, Mavi Vatan emphasizes Türkiye’s expansion and influence in the Mediterranean, Aegean, and the Black Sea through a combination of military and diplomatic means that would enable Türkiye to access energy and other economic resources.

In 2015, President Erdoğan adopted the Blue Homeland Doctrine as part of a national strategy of “forward defense” in the context of his ongoing endeavors to assert Türkiye’s independence in all aspects of foreign policy to include influence in the surrounding regions.[16]

Under this doctrine, Türkiye seems more willing to use military force to implement its vision, objectives, and policy. This has been evidenced by the deployment of Turkish military frigates to secure oil exploration in the eastern Mediterranean, the military intervention in Libya, and the support for allies like Qatar and Azerbaijan with military forces.

Check how the Turkish military industry changed in five years in a previous study by AYAM. [17]

3. Turkish-Russian Relations

Türkiye and Russia have had a turbulent relationship due to their history of conflict. For the most part, the Russian Empire’s ambition to take over parts of the Ottoman Empire, the Bosphorus, and the Dardanelles strait, led to the Twelve Wars that extended for centuries, summarized in Table No. (1).

| War Number | Date | Result |

| 1 | 1568–1570 | Russian military victory |

| 2 | 1676–1681 | – |

| 3 | 1686-1700 | Russia was able to occupy parts of Ottoman territory |

| 4 | 1710-1711 | The victory of the Ottomans and the restoration of occupied territory |

| 5 | 1735-1739 | The Ottomans controlled many areas in Serbia and Belgrade under the Treaty of Belgrade. |

| 6 | 1768-1774 | Russian victory, and control of lands in Crimea |

| 7 | 1787 – 1792 | Russian victory, Ottoman recognition of Crimea to Russia |

| 8 | 1812 | Russia annexed the city of Bessarabia |

| 9 | 1828-1829 | Occupation of the Danubian Principalities by Russia, independence of Greece from the Ottoman Empire |

| 10 | 1853-1856 | The victory of the Ottomans, the British, and the French.Russia ceded Moldova and de jure recognized Ottoman sovereignty over the Danubian Principalities |

| 11 | 1877-1878 | The victory of Russia and its allies, the de jure independence of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro, and the de facto independence of Bulgaria from the Ottoman Empire |

| 12 | World War I 1916 | The victory of the Ottomans and Germany over Russia, and the signing of the treaty of Kars, which returned the lands that were once occupied by Russia. |

The conflict between the interests of the two countries remained between 2015 and 2020. These conflicts were mainly due to Russia’s military expansion in various regions, including Syria, Armenia, the separatist regions of Georgia, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Crimea, and Libya. Justifiably, Türkiye was worried about a military encirclement by Russia.

A golden age followed with the AK Party taking power in Türkiye, and economic ties solidified the relations between the two countries. Indeed, Russia is Türkiye’s top trading partner. In 2019, the two countries’ total trade volume amounted to 26 billion US dollars. The value of Turkish exports was 3.854 billion US dollars, while imports reached 22.454 billion US dollars. In addition, Energy projects such as the Akkuyu nuclear power plant, the TurkStream gas pipeline, and the Blue Streamline form the solid basis for the relations between the two countries. Likewise, the cooperation between Türkiye and Russia in tourism is essential for their bilateral relations. In 2019, over 7 million Russian tourists visited Türkiye.[18]

3.1 The Black Sea Security

The fact that the security of the Black Sea ranks among the constants in Turkish foreign policy sparked several wars with Russia, which sought to reach the warm waters for a long time. Being unable to control the straits, Russia had to sign treaties with Türkiye and other countries to regulate the passage of ships of all shapes and sizes in the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles straits.

Montreux Convention:

The treaty was signed by Türkiye, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, Bulgaria, France, Greece, Romania, and former Yugoslavia in 1936 in Switzerland. It was the last treaty to regulate the transit of ships through the Straits.

Terms of Treaty:

- Authorizing the full Turkish control over the Bosphorus and Dardanelles strait

- Regulating the passage of military vessels

- Ensuring complete freedom of navigation and passage for merchants vessels, under any flag with any cargo, in the straits in peacetime

- Allowing Türkiye to rearm its military on the side or near the straits

- Confirmation of Türkiye’s right to close the strait to foreign warships in times of war or when it is under threat of aggression

- Granting Türkiye the right to refuse the transit of commercial ships on condition that they do not in any way assist the enemy.

- Non-Black-Sea states willing to send a vessel must notify Türkiye 8 days prior of their sought passing

- No more than nine foreign warships, with a total aggregate tonnage of 15,000 tons, may pass at any one time.

- Black Sea states may transit ships of any tonnage, escorted by no more than two destroyers.[19]

“Russia, the former Soviet Union’s heir, is the biggest recipient of the treaty as it owns the most naval and commercial ships and submarines.”

In a related context, The Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014 allowed it to expand its naval capacity and space and shift the strategic balance in its favor, which Türkiye utterly opposed for many reasons:

- Following the occupation of Crimea, Russia’s coastline expanded from 475 km to 1,200 km (about 25%of the total seafront). This is roughly the length of Türkiye’s shores on the Black Sea, which is 1,785 km ( about 35% of the total coastline).

- With its military presence in Crimea, Russia has become geographically closer to the Turkish coast.[20]

- The annexation also raised Türkiye’s concerns about the Crimean Tatars, who hold historically close ties to Türkiye.[21]

In its turn, Türkiye has responded by building up its military forces and encouraging NATO to deploy into the Black Sea, resulting in strategic consequences for both countries.

3.2 Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Russia and Türkiye are profoundly engaged in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. While Moscow has a defense agreement with Armenia[212], Türkiye has a strategic partnership and a mutual support agreement with Azerbaijan and considers their relations as one of the Turkish foreign policy constants.[23]

In April 2016, Nagorno–Karabakh witnessed the worst escalation of violence since the ceasefire was signed in 1994. The Azerbaijani army made minor gains on the ground, but the operations led to heavy losses for both countries. In conjunction, tensions between Türkiye and Russia intensified following Türkiye’s downing of a Russian jet, which triggered a harsh exchange of words between the two countries.[24]

Russia has historically supported Armenia in its disputes with Azerbaijan. However, with the advent of an anti-Russian Armenian government after the revolution of 2018, Russia did not provide enough support to Armenia in the last war with Azerbaijan in late 2020. In contrast, Türkiye helped the Azerbaijan government with military consultations, weapons, and political support, which was enough for the Azerbaijani government to restore several occupied territories.[25]

3.3 Syrian War

Due to its geographic proximity and the growing threat posed by its internal instability, Syria has received a large share of Türkiye’s foreign policy priority. The Turkish-Russian intervention in Syria has greatly impacted their relationship. It started in 2012 as Türkiye supported the opposition to overthrow the Assad regime in Syria, while Russia deployed its forces there in 2015 to support the Syrian regime militarily. The Russian Air Force played a vital role in helping the Syrian regime’s forces, which were able to retake a large portion of the country from the opposition[26]. As a result, the relationship between Türkiye and Russia became strained due to the conflicting interests in the Syrian File and the downing of the Russian fighter by Türkiye in 2015.

In the same year, the two countries managed to overcome their crisis and improve their relations. They also coordinated their efforts in addressing the Syrian issue by offering political agreements such as the Astana and Sochi.[27]

3.4 Economic Relations

Due to Russia’s economic sanctions against Türkiye after the aircraft downing, the two countries’ trade rate decreased by a third, from $23.9 billion in 2015 to $16.8 billion in 2016. The tourism sector experienced the most significant recession, followed by the real estate sector, with a loss of up to ten billion dollars, more than 1% of Türkiye’s GDP. Meanwhile, exports of Russian gas, which account for the bulk of total trade between the two States, continued without restrictions.[28]

In late 2016, Russia lifted most of the economic sanctions imposed on Türkiye, and trade between the two countries increased by 37% in the first half of 2018 to reach $13.3 billion. Turkish exports to Russia rose by 47%, while imports from Russia increased by 36 percent. Furthermore, the Turkish Stream project was reactivated, and the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant was built to generate electricity.[29]

Thereupon, Türkiye and Russia established a joint fund to improve their economic relations. Its objective was to promote trade exchange between the two countries through their local currencies instead of the dollar.

On December 29, 2017, Türkiye strengthened its military defense cooperation with Russia by signing a contract with the Russian state-owned arms company, Almaz Central Design Bureau, to supply two batteries of S-400 missiles[30], which was rejected by the European Union and the United States.[31]

All things considered, Russia ranks as Türkiye’s second-largest economic partner after Germany in infrastructure, transport, energy, agriculture, and tourism.

4. Turkish-US Relations

Over the years, Türkiye has viewed its relations with the U.S. as strategic one. However, the two countries have experienced a significant rift during the past decade due to various disagreements, which kept them, even formally, from the path of their traditional relationship as members of NATO.

The Most Prominent Cases of the Dispute:

4.1 The American Pastor Detention

Andrew Brunson is an American pastor who lived in Türkiye for nearly twenty years and worked in the Izmir Resurrection Church. In October 2016, He was arrested by the Turkish authorities on charges of espionage and having links with the Gülen movement and PKK. In return, the U.S. Department of Treasury imposed sanctions on two ministers in the Turkish government.[32]

In August 2018, following several failed diplomatic efforts to release the pastor, former US President Donald Trump announced a new trade policy regarding the refusal of Turkish aluminum and steel imports. Still, the Turkish government rejected Trump’s arbitrary decision as it contravened the World Trade Organization rules.[33]

Signs of growing distrust between Türkiye and the U.S. reached their climax after the arrest of American and Turkish nationals working in the American consulate, for their links with the Gülen movement, according to the Turkish authorities.[34]

In October 2018, Andrew Brunson was released and returned to the United States. As a result, sanctions against Türkiye were partially lifted[35], but they caused a deterioration of relations between the two countries.

4.2 Gülen’s Extradition Demands

Fethullah Gülen, who has lived in the U.S. since 1999, is considered the mastermind of the 2016 coup attempt. Hence, the Turkish government repeatedly demanded his extradition, but the U.S. government denied it, which exacerbated the tensions between the two.[36]

4.3 S-400 System Crisis

The U.S. rejected the Turkish demands to purchase the American “Patriot” air defense missile systems, which prompted Türkiye to turn to Russia to obtain S-400 air defense missile systems instead.

The U.S. opposed Türkiye’s purchase of the S-400 missile system, claiming it would not be interoperable with NATO’s defense system, in addition to insecurity concerns that the next generation of F-35 fighter jets could be compromised by the S-400 system.[37]

Following Türkiye’s purchase of the S-400 missile system, the U.S. decided to terminate its participation in the F-35 program and threatened to impose economic sanctions against it[38]. At the same time, Türkiye responded that the missile system was necessary to protect its airspace.

4.4 YPG Support

Türkiye has continuously expressed its anger and condemnation of Washington’s support for the PKK terrorist organization’s Syrian wing (YPG) to fight ISIS.

Moreover, Türkiye says the United States has disregarded its national security concerns in its partnership with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) in Syria.[39]

The two countries’ relations became worse after the Turkish Forces’ operations were carried out against the “SDF” units in northwestern Syria in the city of Afrin in 2018 and northeastern Syria in the cities of Jarablus and Ras al-Ain in 2019.[40]

4.5 The American Perspective of the Turkish-Russian Confrontations

Both Türkiye and Russia are on the opposite sides of several military conflicts in different regions, such as Syria, Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan. In this respect, there are various interpretations of the U.S. political vision regarding the Türkiye-Russia confrontation.

– Some believe that Türkiye is a NATO ally, and it can be considered a counterbalance to Russia’s presence in the Middle East. More optimistically, the joint opposition to Russia can also be a basis for reviving the faltering US-Turkish relations.

The statements of former US Ambassador, the United States Special Representative for Syria Engagement, and the Special Envoy to the International military intervention against ISIL James Jeffrey came to confirm this vision.

Jeffrey praised the Turkish role in Idlib and noted that Türkiye’s military mission in Syria could receive financial support from the US or NATO.[41]

– Another opinion states that Türkiye is out of control and is heading towards partnership with Russia in many fields. This idea argues that the growing number of Russian-Turkish bilateral agreements has strengthened the Russian-Turkish relations and is threatening the Western orientation of Türkiye.[42]

5. Türkiye-EU Relations

Türkiye’s relationship with the European Union is one of membership and mutual benefit, and the two sides share many issues related to their national security. Despite the recent dispute between the two parties, the relationship with the EU remains a constant in Türkiye’s foreign policy. Similarly, the EU states still find an important partner in Türkiye in many cases. This was confirmed by President Emmanuel Macron’s statement to the Kathimerini newspaper in September 2017:

“Türkiye had already moved away from the European Union, but I want to avoid the split. Türkiye is a vital partner in addressing the various crises we all face, especially the immigration challenge and the terrorist threat.”

Here, we highlight four major cases that played a role in shaping EU-Türkiye relations between 2015-2020:

5.1 Eastern Mediterranean and Energy Security

In December 2019, the European Council rejected the agreement between Türkiye and Libya regarding the delimitation of the water border between the two countries. The Council noted that this agreement violated the rights of the third parties and affirmed its solidarity with Cyprus and Greece against those actions by Türkiye.

In the same year, Türkiye escalated its security measures, escorting its drilling ships with military vessels in the eastern Mediterranean, a move that sparked strong opposition from the European Union and the threat of severe economic sanctions against Türkiye.[44]

At the request of Cyprus, on July 13, 2020, the foreign ministers of the European Union agreed to prepare additional listings within the framework of the existing sanctions on Türkiye’s drilling operations in the eastern Mediterranean. On July 23, French President Emmanuel Macron demanded EU sanctions against Türkiye’s policy in Greek and Cypriot waters. “I stand fully behind Cyprus and Greece in the face of the Turkish violations of their sovereignty,” said Macron.[45]

Accordingly, France has signed an agreement with Southern Cyprus to service French warships at Marie, the Cypriot naval base.[46] The French President ordered French forces in the eastern Mediterranean to provide military assistance to Greece. France, for the first time, deployed Rafale fighters to help carry out military patrols in the Cypriot exclusive economic zone under a military cooperation agreement.[47]

Meanwhile, Germany’s Foreign Minister Heiko Maas has appealed for de-escalation of tension in the eastern Mediterranean between Greece and Türkiye, warning that it could lead to a disaster. “The two countries are still open to dialogue despite their disagreements,” said Germany’s Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas.[48]

Finally, the European Union’s policy in the Eastern Mediterranean was placed firmly against Turkish interests and rights in its exclusive economic waters due to the convergence of French and Italian (and somewhat German) policies in support of Greece and Greek Cyprus.[49]

5.2 Refugees

Türkiye has witnessed an unprecedented influx of refugees from Syria and other countries— more than 3.7 million as of the date of writing this study.[50] The fact that Türkiye has formed a bridge for many refugees to cross into the European Union pushed the latter to draw up a joint action plan, which was activated at the EU-Türkiye Summit on November 29, 2015. The plan aimed at preventing irregular migration flows to the EU.

In their joint statement of 18 March 2016, the EU and Türkiye have committed to ending irregular migration from Türkiye to Europe, breaking smugglers’ business model, and offering migrants an alternative to risking their lives by heading to Europe.[51]

The future of refugees, mainly Syrians, has been the subject of a constant dialogue between the European Union and Türkiye for more than four years, during which the European Union agreed to pay 6 billion euros to the Turkish government to support Syrian refugees.

However, Türkiye is constantly calling for greater support for embracing refugees in terms of integration, financial, and educational support. Admittedly, some European political parties have expressed that Türkiye should not bear the burden alone, and the financial measures included in the Refugee Support Fund should be expanded.

5.3 Economic Relations

Türkiye and the European Union have a set of mutually beneficial economic interests. There is also a customs union that allows free movement of goods between the parties.

The European Union is Türkiye’s first trading partner and source of investments, while Türkiye ranks as the fifth largest trading partner of the European Union. In numbers, the EU market constitutes 42.4% of the total Turkish exports, while Türkiye’s total imports from the EU reached 32.3%.[52]

| Year | Türkiye’s imports from the European Union | Türkiye’s exports to the European Union |

| 2016 | 72.4 | 55.7 |

| 2017 | 76.7 | 61.4 |

| 2018 | 69.2 | 68.8 |

| 2019 | 68.3 | 69.8 |

As shown in Table (2), Türkiye’s imports decreased by 1.3% in 2019 compared to the previous year, and the proportion of European imports from Türkiye amounted to 4.4% compared to 2018. This is due to the adoption and development of Turkish industries and the production of many goods that Türkiye previously imported.[53]

5.4 Counter-Terrorism

Despite the differences in the priorities of the two sides, counterterrorism cooperation between Türkiye and the European Union will remain a priority. The most critical security concern that has preoccupied both sides in the past five years is the issue of hundreds of ISIS jihadists and their families detained by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units.

Some of the jihadists were arrested by the Turkish authorities on the Syrian-Turkish border, and it turned out that they held European passports. The rest, who are still in Syria, are likely to return to their countries in the European Union via Türkiye. This threat has imposed security cooperation between Türkiye and the European Union, which serves the interests of both parties, and prevents any terrorist acts.[54]

6. Turkish-Saudi Relations

The deteriorating relations between Türkiye and Saudi Arabia were highlighted by the events that occurred between 2015 and 2020. Some of these included the Qatar Crisis and the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul.

On March 13, 2015, the Turkish President expressed Türkiye’s readiness to support the Decisive Storm[55] alliance logistically in the military operation in Yemen against the Houthis.[56]

On April 14, 2016, the Turkish Foreign Minister and his Saudi counterpart signed an agreement to set up a “Strategic Coordination Council” to strengthen eight sectors, including agriculture, the army, culture, combating terrorism, in addition to diplomatic relations.[57]

Six months after the failed coup attempt in Türkiye in 2016, President Erdoğan toured the Gulf, starting with Saudi Arabia and Bahrain.[58]

Then, in June 2017, there was a clear divergence between Türkiye and Saudi Arabia regarding the Qatar blockade.[59] Türkiye’s siding with Qatar and constructing a Turkish military base there provoked Saudi Arabia and negatively impacted the two countries’ relations.[60]

In 2020, things got worse with an “informal” Saudi boycott of Turkish goods. Many Saudi companies, encouraged by the government-linked Saudi Chamber of Commerce, rejected doing business with Türkiye.

On November 20, 2020, King Salman made a phone call with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to invite him to attend the G20 economic summit that was held in Saudi Arabia, and the two sides discussed how to improve the tense relations between the two countries.[61]

7. Turkish-Emirati Relations

The United Arab Emirates was previously ranked among Türkiye’s largest Arab trading partners and was a major source of foreign direct investment. According to statistics, Türkiye’s trade with the UAE decreased sharply after 2017— by 66% in exports and 32% in imports in 2017.[62]

The Arab Spring revolutions indicate that Türkiye and the United Arab Emirates were at odds with one another. While the first supported the revolutions, the UAE was against them. Disagreements between the two parties intensified as Türkiye embraced figures affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which the UAE fought politically and in the media in several countries.

The contention expanded severely between the two countries during the Libyan Crisis. Türkiye stood by the internationally recognized Government of National Accord and supported it militarily and politically. In contrast, the UAE supported Khalifa Haftar’s forces militarily and financially. It is also to be mentioned that the Qatar Crisis and Türkiye’s stance exacerbated the situation.

Moreover, the UAE also stood against Turkish interests in the eastern Mediterranean and organized military exercises with Greece.

Besides, Turkish media always indicate that the UAE played a role in the failed coup in 2016 and spent billions of dollars supporting the Kurdish People’s Protection Units in Syria.[63]

8. Turkish-Iranian Relations

Over the past years, Türkiye and Iran have managed to separate their economic relations from their regional rivalry, which has partially contributed to controlling the mutual policies between the two in order to protect their common economic interests.

To Türkiye, Iran is a strategic source of crude oil and natural gas supplies necessary for its energy security and diversification policy. Iran’s large population also makes it an important market for Türkiye’s exports.

Despite Iran’s criticism of Türkiye’s intervention in Iraq, it does not seem to have any objection when Türkiye carries out a military operation against Kurdish positions in the country.[64] Of course, Türkiye and Iran have a common concern about the independence of Kurdistan in northern Iraq and the establishment of a Kurdish state. [65]

The relationship between the two countries began to be tense with the beginning of the Syrian Revolution in 2015. Iran supported the Assad regime militarily and politically. On the other hand, Türkiye sided with the Syrian opposition. Considerably, each side sought to undermine and condemn the other party’s policy in Syria.[66]

Then, a rapprochement occurred between the two countries after Iran opposed the failed military coup attempt in Türkiye in 2016. Türkiye also criticized the protests in Iran in 2018 and opposed the US sanctions imposed on Iran in the same year.[67]

As a result, cooperation between the two parties increased despite their differences in the Syrian file. In 2017, the Turks met with the Iranians, along with the Russians, in the tripartite meeting in Sochi and then in Astana to sponsor the negotiations between the Syrian opposition and the regime.

9. Turkish-Egyptian Relations

Tensions between Türkiye and Egypt grew after the military coup carried out by current President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi against the elected government in 2013. Despite the tension between the two countries, their diplomatic relations were maintained at the level of Chargés d’affaires.[68]

The two countries enjoy strong economic ties as Egypt is Türkiye’s main trading partner in Africa. Surprisingly, the value of trade exchange between the two parties recorded an increase from 2015 to 2019, despite the political crisis.[69]

| Year | Turkish exports to Egypt | Turkish imports from Egypt |

| 2015 | $2.2 billion | $863 million |

| 2016 | $2 billion | $706 million |

| 2017 | $1.8 billion | $909 million |

| 2018 | $1.9 billion | $1.1 billion |

| 2019 | $2.6 billion | $1 billion |

Table No. (3): Turkish-Egyptian Exports and Imports between 2015 – 2019

Tensions increased between the two countries after Türkiye signed a maritime boundary treaty with Libya in 2019. In response, the Egyptian government rejected and signed a counter-treaty with Greece demarcating their water borders.

Tensions rose after Türkiye militarily intervened on the side of the Government of National Accord against Khalifa Haftar, who is backed by Egypt. Unquestionably, the Turkish military’s support turned the tide of the war in favor of the GNA.

Signs of improved relations began in early 2021 after Türkiye issued instructions to TV channels run by the Egyptian opposition in Istanbul to mitigate its criticism of the Sisi regime. In early May 2021, a Turkish delegation visited Cairo, which gave fresh impetus to the relations between the two.[70]

The return of Turkish-Egyptian relations can be explained by the international transformations, especially in the Middle East. These transformations may result in the American withdrawal from the region, which could leave behind a security vacuum that may be interspersed with the spread of cross-border militias that threaten the countries’ safety.

10. Turkish-Libyan Relations

The former Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit’s visit to Libya in 1979 marked the beginning of the Turkish-Libyan relations. During the time of Muammar Gaddafi, the two countries signed a number of economic agreements in various fields.

More trade agreements to enhance trade exchange were signed in 1987 when former Turkish Prime Minister Kenan Evren visited Libya. Relations between the two countries continued to develop, reaching the highest levels in the late 1990s.

In 2010, The trade exchange amounted to 9.8 billion dollars, and Libya announced that it would grant Türkiye investments of $100 billion.[71]

Türkiye announced its official position supporting mobility and demands for political change iهn the revolution against Gaddafi. After the fall of that regime, the spread of internal chaos, and the militias, Türkiye sided with the legitimate and UN-recognized Government of National Accord, based in Tripoli, against the mutinous Major General Khalifa Haftar.

Based on the Blue Homeland doctrine, Türkiye and the Government of National Accord signed in 2019 the Treaty on the Demarcation of Water Boundaries (Exclusive Economic Zone) in the Eastern Mediterranean. (For more information, see our study on how Türkiye changed in five years, foreign military bases and interventions.)[72]

In 2019, Türkiye intervened militarily in Libya after Haftar’s forces, backed by several international parties, carried out military operations against the Government of National Accord to control Tripoli, the capital, and overthrow the government.

However, the contribution of the Turkish naval and ground forces, backed by drones, enabled the GNA to repel the attacks of Haftar’s forces and regain control of many cities and regions located on the western coastline, in addition to regaining control of many strategic military bases in Libya.[73]

After the formation of a National Unity Government in Libya in 2021, Türkiye maintained its political and economic interests and signed several trade agreements in different fields.

11. A comparison of the Course of Turkish Foreign Relations before and after 2015

| The course of Turkish foreign relations before 2015 | The course of Turkish foreign relations after 2015 | |

| Turkish-Russian Relations | – Strained relationships | – Rapprochement to calm the relations- Coordination in several cases- An increase in the trade exchange index between the two countries |

| Turkish-US Relations | – High coordination between the two countries in all cases | – Disagreements regarding SDF,- Eastern Mediterranean Case- Russian S-400 missile crisis |

| Türkiye-EU Relations | – Almost complete coordination on all levels (political, economic, security…etc) | – Disagreements over the refugee issue- Eastern Mediterranean Case- Libyan Crisis |

| Turkish-Saudi Relations | – Agreement on the Syrian crisis and the position on the Houthis in Yemen | – Severe tension in relations began with the blockade of Qatar. |

| Turkish-Emirati Relations | – Tension since the military coup in Egypt | – Growing disputes over several cases; the blockade of Qatar, Libya, and the UAE’s support for Greece in the eastern Mediterranean |

| Turkish-Iranian Relations | – Disagreement over the Syrian crisis | – Rapprochement and more coordination in the Syrian case |

| Turkish-Egyptian Relations | – Severe tension, as a result of several differences that began with the coup against Mohamed Morsi | – The two countries began exchanging delegations and negotiating to resolve differences |

| Turkish-Libyan Relations | – Maintained diplomatic relations | – Intervene and support the Government of National Accord politically and militarily |

12. Conclusion

The Turkish foreign policy has undergone a significant change in the last five years due to the adoption of the Blue Homeland, the Zero-problems, and Peace at Home, Peace in the world doctrines.

Internationally, there was a dispute over some cases between Türkiye and the United States, especially regarding purchasing the S-400 missiles and Türkiye’s rapprochement with Russia. The differences were somewhat severe, yet Türkiye maintained strategic relations with America.

Türkiye’s relations with the EU were fluctuating and had several differences regarding the delimitation of the water boundary in the eastern Mediterranean, the Libyan crisis, and the refugees’ issue. However, the economic relations were preserved as trade and technology transfer play important roles in both directions.

Despite the severe differences, Türkiye maintains its strategic alliance with the EU and U.S. under the umbrella of NATO, an alliance that is considered one of the constants in its foreign policy.

Notwithstanding their historical enmity, Türkiye and Russia have managed to achieve high trade exchange and reach an agreement on various regional issues. They have also coordinated in many cases, such as Syria, Azerbaijan, Libya, and the Black Sea. However, the competition over the control of the Black Sea is threatening the stability of the foreign policy relationships of Türkiye and Russia, making it hard to reach a stage of a strategic relationship.

Regionally, Turkish relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE became tense after Türkiye stood by Qatar in the blockade imposed on it, and to a greater extent with the UAE due to the dispute over several other cases, resulting in a decline in the mutual economic relations between them.

After a phase of competition for influence in Syria, Türkiye moved to coordinate with Iran, following several developments inside Syria

- References

- Aydın, M., 2003. The Determinants of Turkish Foreign Policy,and Türkiye’s European Vocation. The Review of International Affairs, [online] 3(2). Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233226264_The_Determinants_of_Turkish_Foreign_Policy_and_Türkiye%27s_European_Vocation> [Accessed 22 December 2021].

- Yücel Y. Atatürk İlkeleri – Türk Tarih Kurumu Başkanlığı. Türk Tarih Kurumu. https://www.ttk.gov.tr/belgelerle-tarih/ataturk-ilkeleri-belleten-makale/ . Accessed January 18, 2022.

- Dinç S. ATATÜRKÇÜ DÜŞÜNCE SİSTEMİNE GÖRE MİLLİYETÇİLİK İLKESİ. ÇUKUROVA ÜNİVERSİTESİ TÜRKOLOJİ ARAŞTIRMALARI MERKEZİ. http://turkoloji.cu.edu.tr/ATATURK/arastirmalar/sait_dinc_ataturkcu_dusunce_sistemi_milliyetcilik_ilkesi.pdf . Accessed January 18, 2022.

- https://siyasatarabiya.dohainstitute.org/ar/issue017/Pages/Siyassat17-2015_Naime.pdf

- Baskın, O., 1996. Türk Dış Politikası: Temel İlkeleri ve Soğuk Savaş Ertesindeki Durumu Üzerine Notlar. Ankara Üniversitesi SBF Dergisi, 51(1).

- Türkiye’s Enterprising and Humanitarian Foreign Policy. Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/synopsis-of-the-turkish-foreign-policy.en.mfa . Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Kaya E. Dış Politika Değişimi: * AKP Dönemi Türk Dış Politikası. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313919422_Dis_Politika_Degisimi_AKP_Donemi_Turk_Dis_Politikasi . Published 2015. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Orta Doğu ve Kuzey Afrika Ülkeleri İle İlişkiler. T.C. Dışişleri Bakanlığı. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye_nin-ortadogu-ile-iliskileri.tr.mfa . Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Kurban V. 1950-1960 Yıllarında Türkiye İle Sovyetler Birliği Arasındaki İlişkiler. cttad. 2014; 14(28): 253-282.

- Botas.gov.tr. 2021. Doğal Gaz | BOTAŞ – Boru Hatları İle Petrol Taşıma Anonim Şirketi. [online] Available at: <https://www.botas.gov.tr/Sayfa/dogal-gaz/12> [Accessed 23 December 2021].

- Duman M, Samadov N. Türkiye ile Rusya Federasyonu Arasındaki İktisadi ve Ticari İlişkilerin Yapısı Üzerine Bir İnceleme. Kocaeli Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. 2003;(6):25-47. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/252066 . Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Oran B. Türk Dış Politikası: Temel İlkeleri ve Soğuk Savaş Ertesindeki Durumu Üzerine Notlar. Ankara Üniversitesi SBF Dergisi. 1996; 51(01): -.

- Evci G. Mustafa Kemal tarihe geçen sözünü ilk kez sarf etti: Yurtta sulh cihanda sulh. Milliyet. https://www.milliyet.com.tr/gundem/mustafa-kemal-tarihe-gecen-sozunu-ilk-kez-sarf-etti-yurtta-sulh-cihanda-sulh-6192571 . Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Evci G. Mustafa Kemal tarihe geçen sözünü ilk kez sarf etti: Yurtta sulh cihanda sulh. Milliyet. https://www.milliyet.com.tr/gundem/mustafa-kemal-tarihe-gecen-sozunu-ilk-kez-sarf-etti-yurtta-sulh-cihanda-sulh-6192571 . Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Yeni Dönemde Sıfır Sorun Politikası. T.C. Dışişleri Bakanlığı. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/yeni-donemde-sifir-sorun-politikasi.tr.mfa . Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Kadan T. Mavi Vatan Doktrini Nasıl Oluştu?. Kuşak ve Yol Girişimi Dergisi. 2021;(2(1):35-48. https://briqjournal.com/mavi-vatan-doktrini-nasil-olustu. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- الشاغل ح, الوهيب م. كيف تغيرت تركيا خلال 5 سنوات | تطور الصناعات العسكرية التركية بين عامي 2015 – 2020. مركز الأناضول لدراسات الشرق الأدنى. http://ayam.com.tr/ar/دراسات/industries-develop-turkish-military-between-the-years-2014-2020/.. Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Relations between Türkiye and the Russian Federation. Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-between-Türkiye-and-the-russian-federation.en.mfa. Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- اتفاقية مونترو – ويكيبيديا. Ar.wikipedia.org. https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/اتفاقية_مونترو. Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Russia and Türkiye in the Black Sea and the South Caucasus. Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/western-europemediterranean/Türkiye/250-russia-and-Türkiye-black-sea-and-south-caucasus. Published 2018. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- تركيا: اضطهاد روسيا لتتار القرم مؤسف. Aa.com.tr. https://www.aa.com.tr/ar/تركيا/تركيا-اضطهاد-روسيا-لتتار-القرم-مؤسف-/1978551. Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- أرمينيا وأذربيجان: روسيا تعلن استعدادها تقديم المساعدة “الضرورية” لأرمينيا، إذا وصلت الاشتباكات لأراضيها. BBC News عربي. https://www.bbc.com/arabic/world-54760596 . Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- الشاغل ح, الوهيب م. كيف تغيرت تركيا خلال 5 سنوات | القواعد والتدخلات العسكرية التركية بين عامي 2015 – 2020. مركز الأناضول لدراسات الشرق الأدنى. http://ayam.com.tr/ar/%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%AA/turkish-military-bases-arabic/ . Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- The Nagorno Karabakh Conflict- The Beginning of the Soviet End. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339415817_The_Nagorno_Karabakh_Conflict-_The_Beginning_of_the_Soviet_End . Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- أذربيجان: تركيا ستكون شريكنا الأول في التعاون العسكري ـ الفني. Aa.com.tr. https://www.aa.com.tr/ar/تركيا/أذربيجان-تركيا-ستكون-شريكنا-الأول-في-التعاون-العسكري-ـ-الفني/1941212. Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Abu Nahel O. The implications of the Russian military intervention on the Turkish position of the Syrian crisis. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323202620_ankasat_altdkhl_alskry_alrwsy_ly_almwqf_altrky_mn_alazmt_alswryt_The_implications_of_the_Russian_military_intervention_on_the_Turkish_position_of_the_Syrian_crisis . Published 2017. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- الأزمة السورية.. انطلاق اجتماعات “أستانة-15” في سوتشي. Aa.com.tr. https://www.aa.com.tr/ar/الدول-العربية/الأزمة-السورية-انطلاق-اجتماعات-أستانة-15-في-سوتشي-/2146446. Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Arslan D, Dost P, Wilson G. US-Türkiye relations: From alliance to crisis. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/us-Türkiye-relations-from-alliance-to-crisis/ . Published 2018. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Arslan D, Dost P, Wilson G. US-Türkiye relations: From alliance to crisis. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/us-Türkiye-relations-from-alliance-to-crisis/ . Published 2018. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- S-400 Triumph Air Defence Missile System. Army Technology. https://www.army-technology.com/projects/s-400-triumph-air-defence-missile-system/ . Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- وكالة: صفقة صواريخ روسية جديدة لتركيا ستتم قريبا. Aljazeera.net. https://www.aljazeera.net/news/politics/2019/12/2/وكالة-صفقة-صواريخ-روسية-جديدة-لتركيا. Published 2019. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- أندرو برونسون: القس الأمريكي الذي دفعت تركيا ثمنا باهظاً لاحتجازه. BBC News عربي. https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast-44980773 . Published 2018. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- أنقرة تقاضي واشنطن لدى منظمة التجارة العالمية. Aa.com.tr. https://www.aa.com.tr/ar/تركيا/أنقرة-تقاضي-واشنطن-لدى-منظمة-التجارة-العالمية/1236385. Published 2018. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Arslan D, Dost P, Wilson G. US-Türkiye relations: From alliance to crisis. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/us-Türkiye-relations-from-alliance-to-crisis/ . Published 2018. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Arslan D, Dost P, Wilson G. US-Türkiye relations: From alliance to crisis. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/us-Türkiye-relations-from-alliance-to-crisis/ . Published 2018. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Sırıklı A, Kılıç B. 17-25 Aralık’tan 15 Temmuz’a FETÖ. Aa.com.tr. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/15-temmuz-darbe-girisimi/17-25-araliktan-15-temmuza-feto-/861258 . Published 2017. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- D. أمريكا تحذر تركيا من “تبعات وخيمة محتملة” لاختبار صواريخ إس 400. DW.COM. https://www.dw.com/ar/أمريكا-تحذر-تركيا-من-تبعات-وخيمة-محتملة-لاختبار-صواريخ-إس-400/a-55306281 . Accessed December 23, 2021.

- ماذا يعني خروج تركيا من برنامج F-35?. الحرة. https://www.alhurra.com/choice-alhurra/2019/07/18/يعني-خروج-تركيا-برنامج-f-35؟ . Published 2019. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- لا يتخلون عن دعم PKK.. أوروبا وأمريكا تاريخ طويل من مساندة الإرهاب. Trtarabi.com. https://www.trtarabi.com/now-politics/لا-يتخلون-عن-دعم-pkk-أوروبا-وأمريكا-تاريخ-طويل-من-مساندة-الإرهاب-4459357 . Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- الشاغل ح, الوهيب م. كيف تغيرت تركيا خلال 5 سنوات | القواعد والتدخلات العسكرية التركية بين عامي 2015 – 2020. مركز الأناضول لدراسات الشرق الأدنى. http://ayam.com.tr/ar/دراسات/turkish-military-bases-arabic/ . Published 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- التوتر شمال سوريا.. جيفري في أنقرة للتباحث مع الأتراك. الحرة. https://www.alhurra.com/Türkiye/2020/02/11/التوتر-شمال-سوريا-جيفري-في-أنقرة-للتباحث-مع-الأتراك. Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Makovsky A. Problematic Prospects for US‑Turkish Ties in the Biden Era. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP). https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2020C60/ . Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- ماكرون يطالب باستمرار علاقات الاتحاد الأوروبي وتركيا. Aljazeera.net. https://www.aljazeera.net/news/international/2017/9/7/ماكرون-يطالب-باستمرار-علاقات-الاتحاد. Published 2017. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Tanchum M. Europe: One side of the eastern Mediterranean fault lines – Europe, Türkiye, and new eastern Mediterranean conflict lines – ECFR. Ecfr.eu. https://ecfr.eu/special/eastern_med/europe . Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Macron seeks EU sanctions over Turkish ‘violations’ in Greek waters. http://www.euractiv.com. https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/macron-seeks-eu-sanctions-over-turkish-violations-in-greek-waters/ . Published 2020. Accessed December 23, 2021.

- Tanchum M. Europe: One side of the eastern Mediterranean fault lines – Europe, Türkiye, and new eastern Mediterranean conflict lines – ECFR. Ecfr.eu. https://ecfr.eu/special/eastern_med/europe . Accessed December 23, 2021.